This film has been on my radar forever, but I never actually saw it until this past week. It was one of Those weeks, and it turns out a sweet Bigfoot comedy was just what I needed. It’s also just the thing to round out this chapter of the Bestiary.

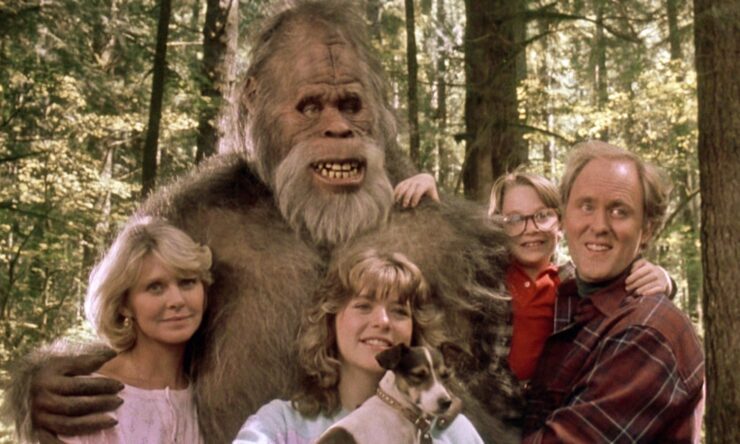

I did not expect to like it as much as I did. It’s a collection of tropes constructed around a very tall guy in a Sasquatch suit. There’s the suburban family with the gun-totin’ dad, the bloodthirsty small boy, the obnoxious teen daughter, and the long-suffering mom.

They’re out on one of their regular camping trips in the Cascades out of Seattle. It’s the last day; they’re about to head home when little Ernie gleefully shoots a rabbit, under dad George’s enthusiastic tutelage. Sister Sarah is totally over it. Mom Nan is just ready to head back to Seattle.

On the way home, on the twisting fire road, with the sun in his eyes, George hits a large, hairy animal. It’s a slow and funny burn as they realize it’s a Bigfoot and decide to load the apparent corpse on the roof of the station wagon and haul it back to the city for fame and glory. And money. Money is a definite factor.

Bigfoot, however, is not dead. One good jump scare and rather a lot of slapstick comedy ensue, not to mention a whole range of chase scenes. There’s a considerable amount of property damage. (Even in 1987, that would have been a serious strain on the homeowners’ insurance.)

The tropes keep on coming. Mega-nosy neighbor Irene sweeps in and out of the Hendersons’ increasingly more dramatically trashed house. Sasquatch-obsessed big-game hunter Jacques LaFleur and washed-out zoologist turned skeevy Sasquatch Museum proprietor Dr. Wrightwood have their separate reasons for wanting to capture the elusive cryptid. A good part of suburban Seattle reacts variously and sometimes wildly to the news of a monster at large in their nice quiet neighborhoods.

A lot of things make it work, but one of the main assets is the cast. John Lithgow is George, Melinda Dillon is Nan, and Lainie Kazan is on point as Irene. Don Ameche imparts a suave and slightly slithery panache to Dr. Wrightwood, and David Suchet is the darkly dangerous LaFleur. But the real star of the show is the big hairy guy—hence, Harry.

Kevin Peter Hall, with stunt double Dawan Scott, was the seven-foot-plus guy in the suit. There was puppetry as well, with a team led by master creature designer Rick Baker. What they created among them was a fully rounded person.

Harry is the North American cousin of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Buddha, the enlightened Yeti from Shambhala. He’s a pescatarian. He mourns the death of warm-blooded animals and gives them a respectful burial. This includes not only the roast for dinner but George’s large collection of taxidermied trophies.

His mourning is beautifully played. He’s a master of the sorrowful-puppy expression. He mimes joy, too, and curiosity. But rarely anger—and then only when severely provoked.

It gradually dawns on the Hendersons that Harry’s vocalizations constitute a language. He understands a fair bit of human speech, and more the longer he spends with them. He is in fact highly intelligent.

Like Buddha, he appears to be some form of human ancestor. He does have one major down side: he reeks. But the Hendersons find a way to fix that.

Their original plan, to get rich off the Bigfoot, transforms into something completely different. Harry teaches them to appreciate the natural world and to feel empathy for the creatures that live in it. He’s an antidote to the macho ideal of George’s dad’s sporting-goods store, which is all about killing things and hanging their remains on walls.

The Hendersons become different people once they’ve met Harry. All but Nan, who was always the most Harry-like of them all. George gets in touch with his real self, which is a talented artist. Ernie turns from killing things to protecting and preserving them. Sarah reveals her true, courageous self. She doesn’t even hesitate to tell off all seven feet plus of Harry when he eats her carefully preserved fifteenth-birthday corsage. She was going to keep that forever. And he ate it.

Never underestimate the power of the teen girl.

Harry is anything but a monster. As always with this version of the Bigfoot story, the real monsters are human.

Humans want to hunt and kill things. They make monsters out of gentle nonhuman beings. When told the truth about Bigfoot, they don’t want to hear it. George’s dad “fixes” the life-size portrait George draws of Harry by giving it scary fangs in place of Harry’s flat, human-like teeth.

The human world, even the one gentled and softened by Harry’s presence, is no place for a Bigfoot. The trope requires that the Hendersons and a couple of unexpected allies return him to the forest. As much as they hate to say goodbye, they have to. There’s no other choice. It’s sad, but it’s also triumphant—especially at the very end, when we see that Harry is by no means the last of his kind.

It’s all about the tropes. It’s as manipulative as hell. And this viewer doesn’t care. Sometimes you just want a big sweet hairy friend to teach you how to be a better person.

Plenty of other people seem to have agreed. The film spawned three seasons of a television series in 1991-1993, when a season was a full 24 episodes. It says a lot for Harry that he could support 72 episodes of commercial television on top of a surprising gem of a film.

I remember watching this movie with my whole family as a kid. I remember we all found it sweet, funny, and endearing. This movie is still my default thought when anyone happens to mention a Bigfoot.

I think a rewatch is overdue.

Same. I recently showed it to my 6 year old nephew. It was just as sweet, funny, and endearing as it was back then. The only difference is I swear the movie I saw as a kid was so much longer, but I know it wasn’t.

I didn’t know there was a TV show, so time to start digging to see where I can check that out!

Wonderful review. Yes, this was a childhood favorite of mine. And yet I also had no idea there was a TV series back then. I’ll have to “hunt” it down. I’m imagining it being like ALF or Small Wonder but… better? Fingers crossed.

Once this movie was available on VHS, our 3-year-old son watched it every day for a year and a half. Everyone in the family soon learned the entire script by heart, and now, some 30 years later, we still quote it.